![]()

Answer to CPC #7 (Wednesday, March 12, 2003)

The radiologic studies demonstrate a small liver that is nodular throughout, and a relatively large spleen; these findings are consistent with cirrhosis. Ascites is identified, but there is no evidence of portal or hepatic vein thrombosis.

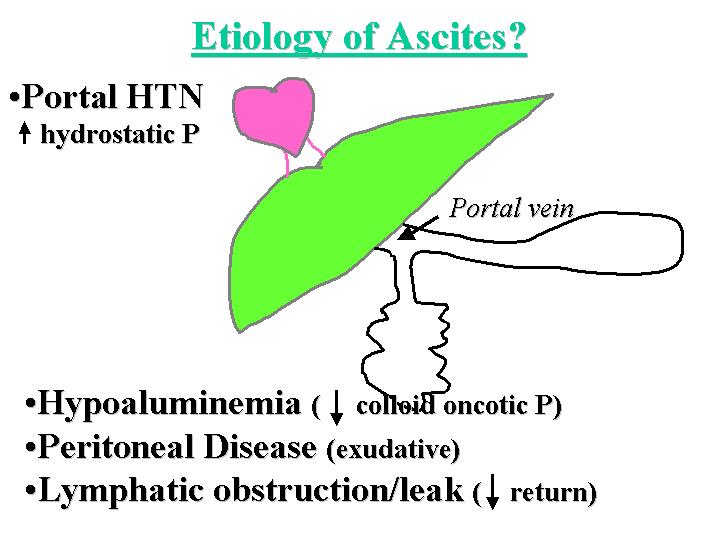

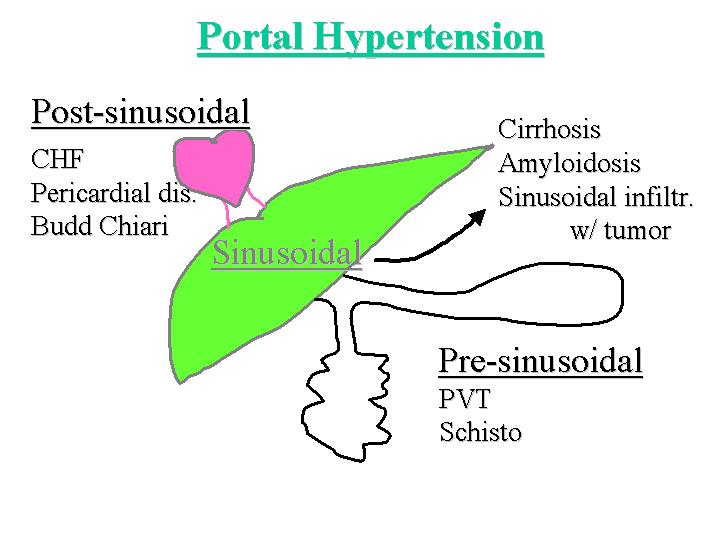

The first question to be answered is what is the etiology of the patient's ascites. Ascites may be caused by portal hypertension (increased hydrostatic pressure), hypoalbuminemia (decreased colloid oncotic pressure), peritoneal disease (an exudative process) or lymphatic obstruction and leakage (decreased return of fluid from the peritoneal cavity) (Figure 1). In this patient, hypoalbuminemia certainly plays a role. Peritoneal disease is difficult to exclude, given the abdominal pain, but less likely given the absence of demonstrable peritoneal disease on imaging studies. Cardiac disease as a cause for lymphatic obstruction is also difficult to exclude, given that the patient was hypotensive despite fluid boluses. Nonetheless, portal hypertension seems to be a major contributor to the ascites here. Portal hypertension may result from three mechanisms, depending upon the location of the obstruction of portal flow (Figure 2). The obstruction of flow may be pre-sinusoidal, as is caused by portal vein thrombosis, or infections which localize to the portal tract, such as schistomiasis. The obstruction may be post-sinusoidal, as in patients with congestive heart failure (which is difficult to exclude in this case), pericardial disease, or Budd-Chiari Syndrome; the latter is essentially excluded by the imaging studies. The other cause of obstruction is sinusoidal disease, for which cirrhosis is the main etiology. Our patient clearly has cirrhosis, given the evidence of hyperammonemia, jaundice and poor hepatic synthetic function (manifested by hypoalbuminemia and coagulopathy), in the presence of the characteristic imaging findings. Other sinusoidal causes of portal hypertension include sinusoidal infiltration by amyloidosis or by tumor cells, such as the blasts of acute leukemia.

Figure 1

Figure 2

Given that we have established that the patient has chronic liver disease (as evidenced by the chronicity of his symptoms), the next question becomes: What is the etiology? The most common causes of chronic liver disease in this country include alcoholism, viral hepatitis and non-alcohol steatohepatitis. None of these is likely in this case given the absence of alcohol abuse, risk factors for viral hepatitis, diabetes or obesity (the latter two predispose to non-alcoholic steatohepatitis). Autoimmune hepatitis is typically associated with hypergammaglobulinemia, and occurs predominantly in female patients. Primary biliary cirrhosis and primary sclerosing cholangitis cause a more obstructive picture on liver function tests and do not lead to fulminant hepatic failure.

The most likely cause of liver dysfunction in this patient is congenital, given the striking family history. Congenital causes of liver disease include Wilson's disease, hemochromatosis, alpha-1 anti-trypsin deficiency, and hereditary tyrosinemia. All of these, except for Wilson's disease are clinically indolent diseases that do not lead to fulminant hepatic failure. Wilson's Disease is an autosomal recessive disorder characterized by spontaneous mutations leading to loss of function of the ATPase 7B copper transporter. This leads to copper retention in the liver, brain, kidney, heart and eyes. The dominant clinical presentations are either neurologic (personality, motor or autonomic disorders) or hepatic (hepatitis, cirrhosis, fulminant hepatic failure or hepatocellular carcinoma). A very high serum ammonia level is characteristic of Wilson's disease. Characteristic ocular manifestations include Kayser-Fleischer rings due to deposition of copper in Descemet's membrane in the eyes, or sunflower cataracts. Osteoporosis, renal stones, renal tubular acidosis, or cardiac arrythmias may also ensue.

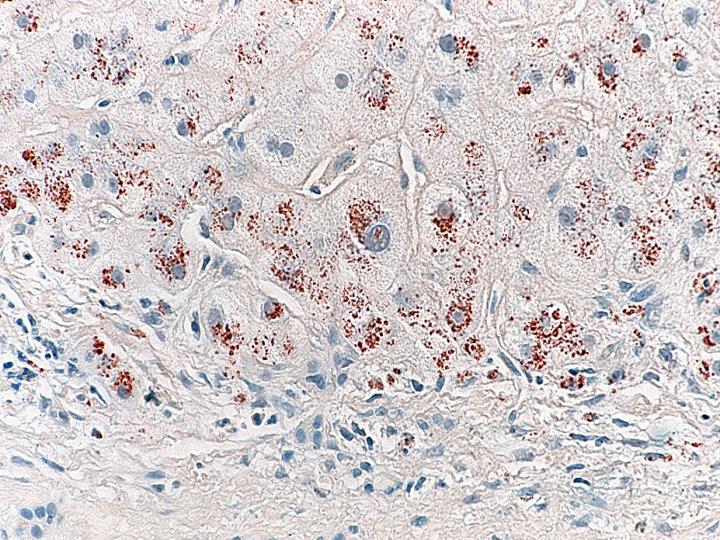

Finding evidence of copper overload supports the diagnosis of Wilson's disease. However, it is important to realize that copper overload can result from any cause of biliary obstruction (copper is normally excreted by the bile) and hence is not specific for Wilson's disease. Tests that can be used to identify copper overload include a high urine copper level, a high non-ceruloplasmin copper level (In Wilson's disease, the hepatic copper is not stored in the golgi apparatus as it usually is, leading to inappropriately low ceruloplasmin production by the hepatocytes), and increased hepatic copper. Increased hepatic copper can be determined by copper stains (typically the orcein or rhodamine stain) or by quantitative evidence of copper overload using mass spectrometry.

Therapy for Wilsons Disease can be divided into treatment for pre-symptomatic patients, symptomatic patients and those in fulminant hepatic failure. Pre-symptomatic patients are treated by dietary restriction, so that intake of foods such as chocolate, which contain abundant copper, is discouraged. Treatment with zinc can help inhibit copper absorption, and patients may also be treated with D-penicillamine, a copper chelator. Unfortunately, D-penicillamine leads to abnormalities in collagen integrity and therefore leads to cutaneous abnormalities. Symptomatic patients must be treated with D-penicillamine. Patients are usually given pyridoxine supplements along with D-penicillamine, as the latter may otherwise cause pyridoxine deficiency. Treatment for fulminant hepatic failure is supportive care and liver transplantation if the patient is able to tolerate this potentially life-saving procedure.

The cause of the patient's acute deterioration is the final question. Assuming the patient has Wilson's disease, a flare of the Wilson's disease could lead to acute and fulminant hepatic failure. One must also exclude a superimposed insult, such as the development of hepatocellular carcinoma, infection (specifically, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis), and hypoperfusion from shock. Finally, D-penicillamine itself can also be a toxin that can promote acute deterioration.

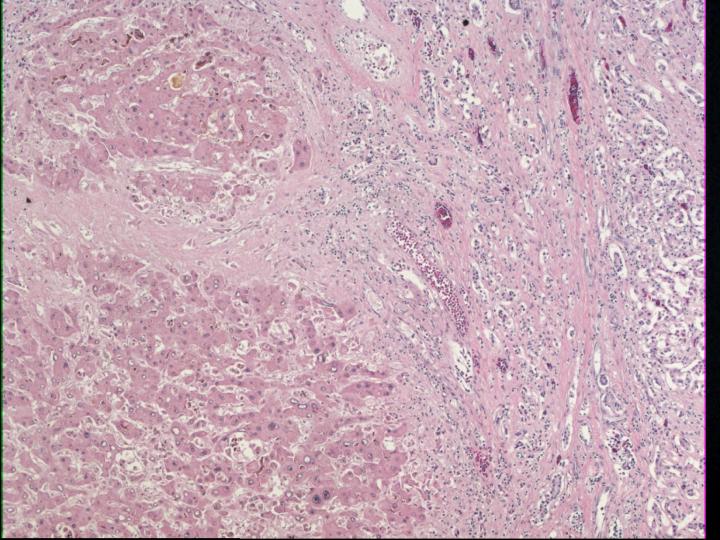

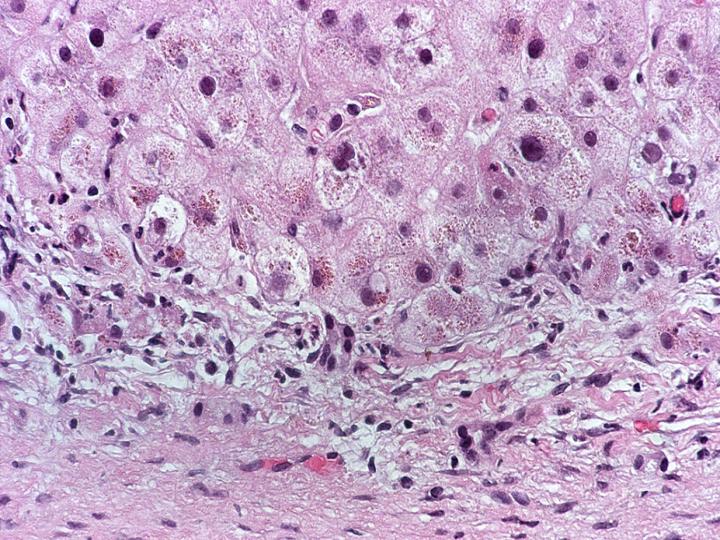

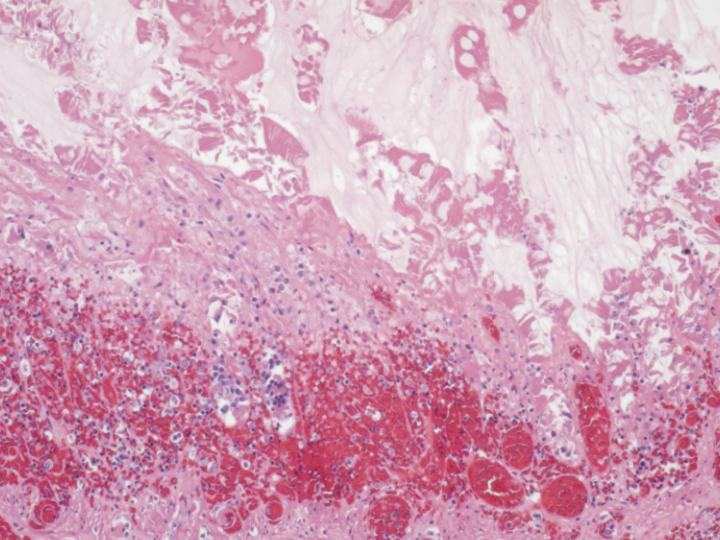

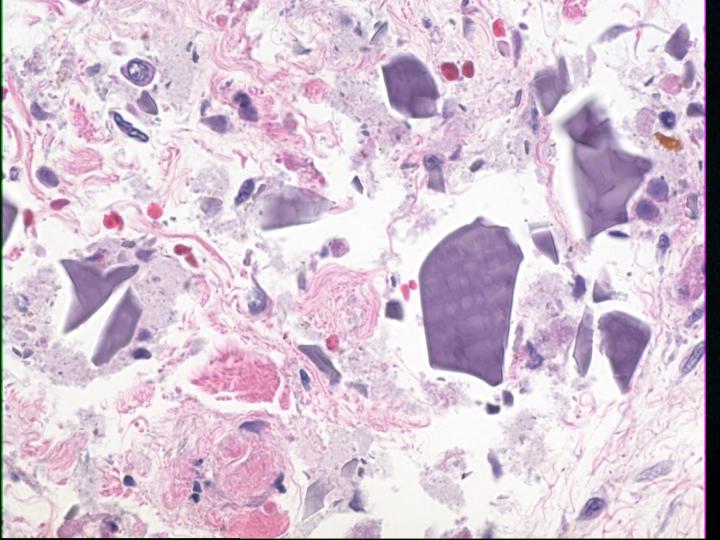

This patient underwent autopsy at which time the liver was noted to be grossly cirrhotic. Histologic sections confirmed cirrhosis (Figure 3), defined as diffuse bridging fibrosis involving the liver with accompanying regenerative nodules. Close inspection of the cytoplasm of the hepatocytes within the liver yielded evidence of fine red granules, which is typical of copper deposition (Figure 4). This was confirmed by a rhodamine stain (Figure 5). Other findings in the autopsy included foci of bowel necrosis (Figure 6) along with Kayexelate deposition. The latter is identified on the histologic sections as crystalline particulate material with a scale-like appearance (Figure 7).

Figure 3

Figure 4

Figure 5

Figure 6

Figure 7

In summary, this patient expired from Wilson's disease, one of the more common causes of congenital liver disease, and one associated with many different clinical presentations.